Modern Feminism: The Role of Women in Music

(Photo credit: Depositphotos.com)

I hate to even bring it up again, but remember Miley Cyrus’ performance at the 2013 MTV Video Music Awards? The one with twerking teddy bears and misappropriated foam fingers, the one that, if they weren’t watching it already, sent every soon-to-be-outraged talking head to the Internet to see what they’d missed?

In retrospect, Cyrus’ nude-bikini-clad tongue-wagging was a key moment for women in pop music this past year – at least, it was certainly one of the most memorable. Her complete one-eighty from twee Disney starlet to lascivious media whore (and I do mean whore in the most sex-positive way possible, as a fully conscientious and consenting adult accepting payment for what she does with her body for a living) is in some ways predictable, following in the good-girl-gone-bad footsteps of the likes of Britney and Christina, but at the same time opens up new and challenging conversations about the ever-evolving roles of women in popular music.

Take the infamous exchange of open letters between Miley and the notoriously open-mouthed singer-songwriter Sinéad O’Connor. After Cyrus cited her as an inspiration in a Rolling Stone interview, O’Connor wrote, “in the spirit of motherliness and with love,” a plea to Cyrus not to allow herself to be prostituted by the music industry. “Real empowerment of yourself as a woman would be to in the future refuse to exploit your body or your sexuality in order for men to make money from you,” she wrote.

Cyrus’ responses were flippant, and she denies acting as a role model for anyone – including her largely young-teens female fanbase. But that’s just the thing: as minorities in the music business, women out front-and-center like Miley serve as representatives for the population at large, whether they intend to or not. They serve to inform other females about culturally acceptable modes of behavior and how to express their sexuality while at the same time teaching men what to expect and/or desire from women.

Cyrus’ tactic is especially complicated: Yes, she seems to insinuate oral sex with just about every inanimate object she comes across and her appropriation of Black culture can be read as exploitative, but her brand of female sexuality is also fresh, in a way. It’s both calculated and aggressive. She eschews some (but certainly not all) traditional beauty standards and does away completely with the whole innocent-little-girls-are-sexy thing that plagued Britney Spears and many more along with her for so long. Cyrus is not innocent, and she wants you to count the ways.

Unlike the interchangeable pop divas of music eras past, Cyrus is breaking the mould – and legions of female artists are right along with her. The year 2013 saw a massive outpouring of music from women in all genres from rap to indie rock to country, and with it a growing sense of respect from the male-dominated biz. Outside of blockbuster Top 40 radio pop, female artists have been historically marginalized or othered, placed in some separate-but-equal ranks where “female singer-songwriter” is somehow a different category from “singer-songwriter.” But in 2013, many Best-Of year-end round-ups had a strong showing of women on top – not as tokens, not with any qualifiers or asterisks, but judged equally alongside their male peers. Beyoncé’s self-titled surprise drop was named Billboard’s album of the year; Kacey Musgraves won a Grammy for Best Country Album; Paste magazine named Janelle Monáe’s “Q.U.E.E.N.” best single of the year.

New talents, too, pepper the lists of industry faves, from 17-year-old Lorde to post-punk rockers Savages, and from Scottish electro-pop group CHVRCHES to So-Cal sister-rock Haim. The new multitude of faces actually gives young girls – and boys – options of where to look on how to be a rock star. Too often, female performers are judged first by their gender, second by their appearance, and only third by their art. But at least for this past year, the boys’ club of the music media industry has arrived at near-equal representation of women; girl-fronted groups or artists sometimes made up nearly half of any given mag’s Top-10 list. We’re past relegating songs made by women as strictly for women, or solely comparing female artists to other females, or judging a woman’s stage presence by how good she looks in a pleather bodysuit.

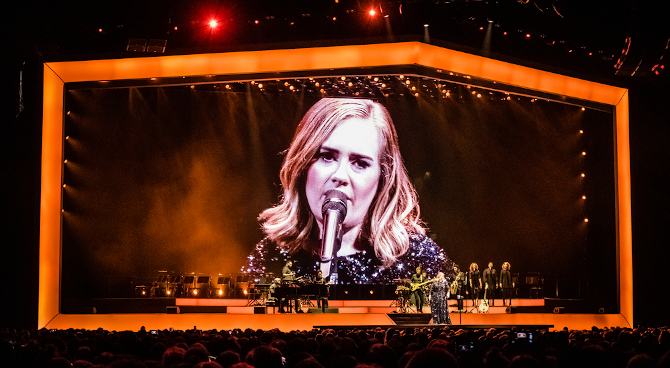

Which is not to say that sexism has gone and disappeared completely from the music biz, or the music coverage biz. Take, for example, a 2012 cover story from the New York Times’ T magazine, where the author described songstress Lana Del Rey as “a skinnier Adele, a more stable Amy Winehouse.” (“We’re a gender, not a genre,” says Adele.) Both Savages and Haim recall early gigs where sound technicians dismissed them as a girl group, later apologizing to the effect of “Sorry, I didn’t realize you were going to be good.” Canadian singer Grimes took to her tumblr, tired of men who act “as if the fact that I’m a woman makes me incapable of using technology. I have never seen this kind of thing happen to any of my male peers.” She also writes: “I don’t want to be molested at shows or on the street by people who perceive me as an object that exists for their personal satisfaction.”

(Photo credit: Depositphotos.com)

In September, CHVRCHES frontperson Lauren Mayberry came forward in an article for the Guardian with the same attitude as Grimes, detailing the misogynistic, offensive, lewd, and even threatening online messages she receives daily from anonymous or unknown men. She denies the oft-held response that it’s just something that comes with the territory of being in a successful band in the public eye, especially in the age of the Internet. “Is the casual objectification of women so commonplace that we should all just suck it up, roll over and accept defeat?” Mayberry writes. “I hope not. Objectification, whatever its form, is not something anyone should have to ‘just deal with.’”

The conversation about women’s representation in music media came to a head in November with Lily Allen’s controversial video for “Hard Out Here.” The song’s lyrics criticize many of the double standards about sexuality, ambition, and physical appearances faced by women not just in the music industry, but in everyday life. The video is meant as a parody, but Allen’s backup dancers – all of them skinny, conventionally beautiful, scantily clad black women – twerk and grind pretty much the same way you’d see in any modern MTV video. Few visual ethics are challenged, and the treatment isn’t absurd enough to be satirical. As a white woman directing black dancers, Allen (unintentionally) turns the focus instead on racial oppression – something that Miley’s been equally accused of with her stage show.

Meanwhile, Allen sings, “Don’t need to shake my ass for you ‘cause I’ve got a brain.” No doubt she meant to empower women and young girls, to put out the message that a female is more than the sum of her, um, parts. But in doing so, she denigrates the very women around her whose sexuality is a celebrated part of their livelihood – her own dancers, her peers like Rihanna and Beyoncé, or even the young college girl stripping her way through college. Modern feminism means embracing women of all races, shapes, orientations, and occupations. It means that there is no right or wrong way to act as a woman, so long as she’s acting of her own accord. The girl-on-girl judgments, scrutiny, and slut-shamings, even when touted under the brand of feminism, are just as detrimental to achieving equality for all women in a patriarchal society.

The music world needs representation of lady rockers, punks, rappers, crooners, drummers, and even writers, publicists, engineers, A&R reps, label execs, and producers. Billboard’s annual Women in Music feature on the faces behind the scenes is starting to read less like an exhaustive list of females in the business and more, as they say, “like a roster of the top people in the music business who happen to be women.” The scene for women, on-stage and off, is growing: Instead of a Britney vs. Christina camp, girls can aspire to be as fierce as Beyoncé, as cool as Janelle Monáe, as bold as Adele, or as savvy as Atlantic Records COO Julie Greenwald. They can combine their talents, mix-and-match personalities, to find a purpose that is all their own. The point is that they have a choice.

Author Bio:

Sandra Canosa is Highbrow Magazine’s Chief Music Critic.

For Highbrow Magazine