‘The Death Tour’ Deftly Portrays Ambitious Wrestlers Vying for Fame and Glory

Growing up, I always had a fascination with the art of wrestling. Something was alluring about the theatrics of the performance. Wrestling understood the fundamentals of storytelling. You had clearly defined characters with specific narrative roles. The faces were the good guys, and the heels were the bad guys. The heel’s primary job is to make the face look good, until audiences get bored of that storyline, leading to a face becoming a heel, and vice versa. It’s a Shakespearean tragedy when you think about it. Yet, behind the wigs, rock music, and baby oil, lies a foundation built on sacrifice.

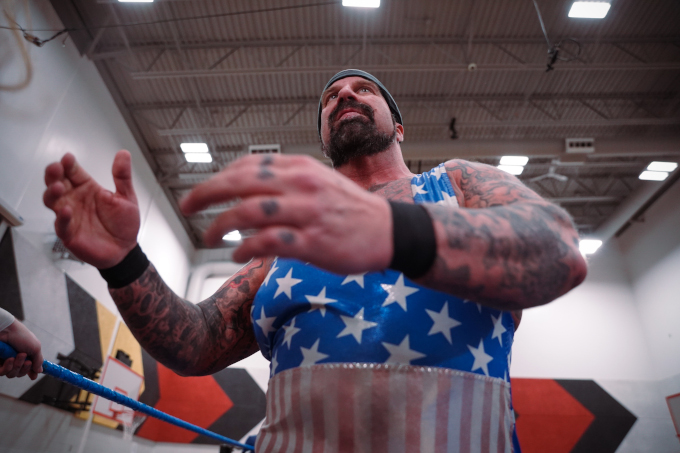

Every winter as Northern Canada freezes over, a handful of wrestlers heads to the remote indigenous communities of Northern Manitoba and competes in The Death Tour. It is a three-week battle of endurance as these amateur wrestlers get their first big break to compete against their competition and the elements to prove they have the goods. Within the Inuit communities, there is no lounging, thus the wrestlers must pack their sleeping bags and sleep on the floor of the gymnasium in sub-zero degree temperatures. If this sounds crazy, it is because it is. Yet, some of the biggest names in wrestling made their name at The Death Tour, including executive producer Chris Jericho, who along with the filmmaking team of Stephan Peterson and Sonya Ballantyne, offers firsthand accounts of what it means to compete in this endurance of mental and physical strength.

The Death Tour follows wrestlers as they partake to see if they have what it takes to achieve glory. The documentary captures the human psyche of a wrestler’s profile, and why they choose to compete. Some are driven by the idea of fame and glory. Others embark to see if they still have the spirit of a fighter within. And in some cases, The Death Tour offers the ability to connect with their communities and heritage. Yet, what brings them all together is their determination. The Death Wish is able to explore stories about the human condition as tested by the elements, all while capturing the cathartic nature of pain.

Yet, the film succeeds not only because of its investment in self-realization but also its keen interest in the Inuit community. As a child raised in the Misipawistik Cree Nation, filmmaker Sonya Ballantyne saw the story of The Death Tour as an opportunity to explore the culture of the remote Indigenous communities of Northern Manitoba, and how these two worlds collide every winter. In doing so, we see how these two unlikely groups come together and relate to one another. Counterbalanced with the backdrop of the world of professional wrestling, Peterson and Ballantyne create a beautiful ballet that explores identity, representation, and the strength required to fight to be seen.

Occasionally, The Death Tour suffers from being too “insider baseball.” As familiar as I am with the broad strokes of wrestling, aspects of this world still leave me puzzled, and I can’t say the film spends much time trying to make the world of wrestling accessible for people unfamiliar with the sport. And maybe, that is intentional. In a history written by the conquerors that forced their oppressed to adapt, this documentary exists to display a community proudly aware of its identity and interests, without any care of what others think or don’t understand.

Author Bio:

Ben Friedman is a contributing writer and film critic at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine