Defying Censors: Breaking Bad of the Chinese Language

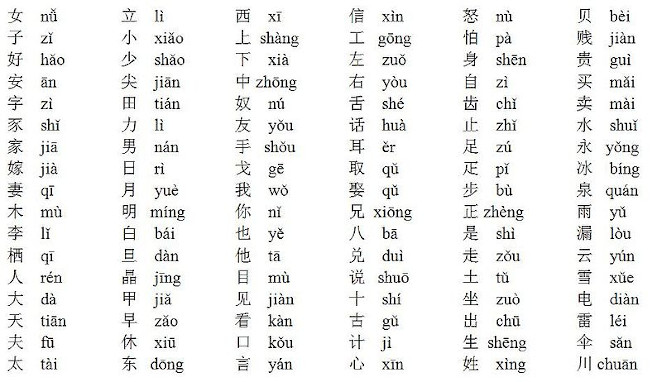

The other day I was chatting with a childhood friend on China’s version of WhatsApp or Telegram, known as WeChat. At one point I had to make a reference to the biblical flooding that befell Beijing and its surrounding area recently -- such a tragedy or, in Chinese, such a beiju. As we all know, Chinese – Mandarin, Cantonese, or any other dialect -- is not a phonetic language. I could not just type the romanized literation of beiju. Words must be represented as Chinese characters. I typed “杯具” (cups and glasses) instead of “悲剧” (tragedy). I could get away with it because they are pronounced the same way. And my friend needed no extra hit to pick up the meaning behind “cups and glasses.”

Misspelling, as I did with the word “tragedy,” is just one of many techniques today’s Chinese netizens employ to evade the government’s dragnet of online censorship. When the flood was raging, words like “tragedy” immediately made their way into the censor’s dictionary of sensitive words and were blocked. Why would the government not block its homophone cups and glasses then? Because the Chinese language is full of ubiquitous homophones. Without seeing what is written in Chinese characters to represent the pronunciation of beiju, it is literally a wild guess to decipher the meaning. It could mean the encounter of a rejection, or a residence in the north. The censor would have to paralyze the language in its entirety in order to block all possible homophones of sensitive words on their ever-growing long list.

The linguistic purist in me feels guilty when I butcher the Chinese language to evade censorship and to enjoy a momentary freedom of expression. I know my elementary Chinese teacher, known for her short temper and fierce nickname of Dragon Lady – may she rest in peace – would have hissed at me if she saw how badly I spell in online chat and posts nowadays. I cannot bear imagining the trauma she would sustain if she witnessed the deliberate and ruthless surgery I perform on the language to get my message across. I’m sorry Dragon Lady, but the Chinese zeitgeist is a linguistic surgeon hellbent on malpractice.

The freedom-fighter in me, on the other hand, delights in the mutilation and encryption of Chinese vocabulary and grammar. Damn, it feels good to break bad when you do Chinese netspeak: the joy of saying something cryptic and knowing your message will get across. The schadenfreude of sending the censor into a maze collectively designed by the 1 billion ingenious Chinese netizens. The intricate nooks and crannies of this guilty pleasure are impossible to translate to an English speaker, but I thought I should at least make a valiant attempt anyway.

Here is a short but far-from-exhaustive list of ways a Chinese speaker can participate in the breaking bad of the Chinese language:

Use the passive voice where it is grammatically inappropriate. This is one popular way of hinting at the sinister nature of the action you are describing. For example, if you are fired from a job and forbidden to complain about it, you can force a grammatically incorrect passive voice on the verb “quit.” You would say something like, “I was suddenly resigned by my boss the other day.” Or if a Chinese Communist Party official in your apartment building jumped out of his window and killed himself in the midst of a criminal investigation, you can simply regale the story as “a cadre was suicided by jumping out of the window,” and everyone would know there was a visible or invisible hand that pushed him out of the window.

Use euphemisms. Don’t refer to things by their real names. Use clever euphemisms. This means you would refer to China as hell of a country and the United States as the hell of fire and flood to amplify the irony in the government’s propaganda. What if the subject matter does not have a widely accepted euphemism? Well, that is when you misspell and take advantage of a homophone.

Break a character into two. The leader of North Korea, Kim Jung-un, is commonly referred to as Fat Guy Number Three after his father (Number Two) and his grandfather (Number One) among Chinese. However, the character for “fat” can be broken into two component characters (known as radicals) and those two subcharacters are “month” and “half.” Therefore, if someone says something about “Three Month and Half,” it is a reference to the leader of China’s neighbor.

Speak Chinglish. The Chinese government has long replaced the Wade-Giles romanization of Chinese words with a system called pinyin. Pinyin got rid of a lot of quirky literation like “hsie” and “tse” and “jongg” that are not found in common English words and made it easier for Chinese to learn. By the same taken, it creates a great deal of Chinese words whose romanized literation happen to mean something in English. The prime example is the Chinese word 润 (to lubricate) whose pinyin is spelt as run. And nowadays, the word 润 basically has lost its original Chinese meaning. Instead, everyone understands its adopted English meaning of “running.” And by logical extension, the meaning of “leave,” “escape,” or “immigrate.”

Use numerals. Just as the Japanese word Yakuza is “893,” today’s Chinese netspeak is full of cryptic numerals. “94” is used when someone agrees with you, because it sounds similar to the phrase “I agree” when you say it. “996” is the code for a salaryman’s lifestyle and means your work hours are 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week. If Portuguese speakers can understand a story written exclusively in verbs, an experienced Chinese netizen can understand a long paragraph of nothing but a bunch of numerals.

Extreme plain speak. Today’s Chinese use vocabulary that are void of the language’s ancestral and intrinsic abstraction. The netizens talk like they have just graduated from a government-sponsored adult literacy night school. The phrases in high volume of circulation are deliberately unrefined. It follows the formula of saying as little as possible and understating it as much as possible but meaning as much as the listeners can conjure. Phrases like “lying down” mean far beyond the act of staying supine. It is rather the Slackers Manifesto of “Sorry, our dear Party, but I don’t feel like participating in your stupid game anymore.”

I have met Americans who learned Chinese from ivy league universities back in the 1970s, following Henry Kissinger’s zealous suggestion. To members of that movement who have not kept up with the language, Chinese has evolved into a cyber lingua franca that demands a Mao-style rude re-education.

But I am digging the “breaking bad” of my mother tongue, and I wish non-Chinese speakers can also appreciate this as much as I do.

Author Bio:

Peter Chang is a pen name used by the author of this article.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Thirdman (Pexels, Creative Commons)

--Tookapic (Pixabay, Creative Commons)

--Alphabets alphabetical (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons)

--Needpix (Creative Commons)