China’s Two Sessions: No Solid Plan for the Economy

On March 11 in Beijing, the Chinese government concluded its annual Two Sessions, the pivotal planning event of the year, comprising the National People's Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). These sessions convene around 3,000 delegates nationwide to deliberate on critical legislative and political matters, proposing policies and advising the government to foster consensus and steer the nation's development.

While the sessions are ostensibly aimed at consultation, in practice, major decisions are predetermined before convening, serving primarily to brief delegates on their annual objectives. Subsequently, delegates must return to their constituencies and decide how to achieve their targets.

Each year, governments around the world monitor the Two Sessions to see what China has planned for the coming year. This year is of particular interest because China is in the worst state economically and diplomatically that it has been in for several decades.

China’s economic growth was driven into the doldrums by extreme COVID lockdowns, which finally ended in January 2023. Even before COVID, China was facing one of the largest debt-to-GDP ratios on the planet. At the same time, its real estate sector had become a massive bubble, which, when it burst, threatened to take the banking sector with it. After the first few months of the pandemic in 2020, the diplomatic tide began to turn on China. Beijing was selling PPE and medical supplies to countries and claiming that it had donated aid.

Much of the equipment countries purchased from China was defective. The United Front Work Department of the Chinese Communist Party was also hard at work rolling out propaganda videos and pushing narratives online that portrayed China as a savior. During lockdowns, poor countries and their populations suffered greatly from an inability to work and earn money. Many of these countries were already heavily indebted to China as a result of participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Now, the reality of the high interest China was charging on the loans was driving home the fact that the promised gains to GDP never materialized. The Wilson Center estimates that a full 80% of government BRI loans have gone to countries in debt distress.

The trade war with the United States expanded, taking another bite out of both China’s income and its global standing. Additionally, China officially shifted its foreign policy from a “charm offensive” to “wolf warrior diplomacy” as Xi Jinping became more aggressive about claiming territory in the South China Sea and threatening to take Taiwan by force. Currently, apart from Taiwan, Beijing has sea territory disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, in addition to land border disputes with Bhutan, India, and Nepal.

The dispute with India is significant because India is a member of the BRICS grouping and now the world’s largest country by population. Xi Jinping’s hopes that India would come into the Chinese sphere of influence seem less likely, especially after Beijing published a new map showing Indian territory as already belonging to China.

The Ukraine War became a catalyst for countries stepping away from China because of Beijing’s support for Russia. This accelerated reshoring, friend-shoring, and rerouting of supply chains to avoid China. And this was not just for the US but also Europe. At the G-7 meeting last year, the world’s leading economies discussed derisking from China. At the same time, the manufacturing and exporting that has left China has given an economic boost to countries like Vietnam, India, and Indonesia, which were already experiencing strained relations with China.

At the close of 2023, China’s net investment was negative, meaning more money was flowing out than in. Industrial activity is trending down, the country is experiencing deflation, the real estate bubble has started to slowly burst as some of the larger developers have been forced into bankruptcy, and youth unemployment remains at record levels. Debt to GDP stands at more than 287%. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index, considered a benchmark of overall economic performance and confidence, has lost nearly 20% over the past year. According to recent polls, about two-thirds of the world’s population has a negative opinion of China.

Against this backdrop of negative indicators, the Two Sessions has set a GDP growth target of 5%, which would be astronomical for a developed economy but is considered low for a developing country, particularly given that China still had double-digit growth just over a decade ago. What’s more, many experts are skeptical that China will hit this modest target given all of the problems it is struggling with.

Beijing announced plans to use central planning to support the industrial sector, revamping equipment, and increasing productivity. There will also be a push for high-tech and self-reliance, which is meant to be achieved through an allocation of $51.6 billion in government funding. Additionally, the Minister of Housing and Urban-Rural Development said that the central government would not bail out developers, and those in distress will be allowed to go bankrupt. Beijing announced stimulus that would be funded with $139 billion of ultra-long government bonds. This raises questions about how China will deal with the additional debt burden.

Normally, at the end of the conference, the Chinese premier, who is responsible for the economy, would hold a press conference. This year, the press conference was canceled, raising eyebrows and casting doubt about Beijing’s confidence in achieving its 5% growth goals. Normally, the property sector is a pillar of growth, but Beijing will not be coming to the rescue. It may also be that Beijing does not wish to address questions about how allowing the property developers -- who represent over 20% of the economy -- to collapse would not cause a chain reaction, which would sink the rest of the economy.

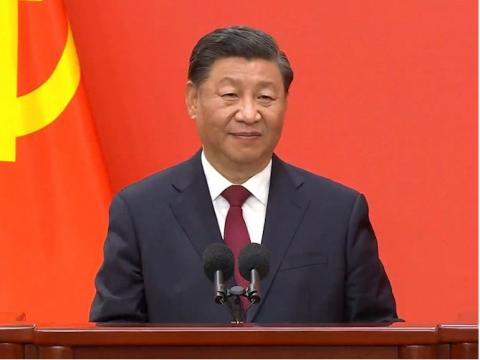

The final takeaway from the Two Sessions is that Xi has further consolidated his power, as economic decision-making will now be done by high-level Communist Party bodies, headed by Xi.

Author Bio:

Antonio Graceffo, a Highbrow Magazine contributor, is a Ph.D. and also holds a China-MBA from Shanghai Jiaotong University. He works as an economics professor and China economic analyst, writing for various international media. Some of his books include: The Wrestler’s Dissertation, Warrior Odyssey, Beyond the Belt and Road: China’s Global Economic Expansion, and A Short Course on the Chinese Economy.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Depositphotos.com; China News Service (Wikimedia Commons)