The Invisible People of Mexico

Not everyone in Mexico is Spanish and indigenous (mestizo). Black people have been a significant part of the post-Columbian history of Mexico and even contributed to the founding of the modern Mexican Republic. Mexico, just like every Latin American country, has indigenous, Black, and European people. During the Transatlantic slave trade, the Spanish forced about 500,000 enslaved Black people to Mexico. In the 16th century, Black Mexicans outnumbered Spanish colonialists. Today, in Brazil, 50.7 percent of the population is Black, which means that it has the second highest Black population of any country in the world, after Nigeria.

According to a 2015 study conducted by the Mexican government, there are 1.9 million Black Mexicans. This figure, however, does not include the people who are mixed race and have African ancestry but do not identify as Black. In the 2020 census, for the first time, citizens will be able to identify themselves as “Afro-Mexican.”

When most of us think about the Spanish conquest of Mexico, the perception is that the conflict was between the native people and Spaniards. But Black people can trace their roots in Mexico to the same day in February 1519, when Hernán Cortés, with 610 Europeans and 300 enslaved people, consisting of African and indigenous Cubans, landed at Cozumel to begin the conquest of the Yucatan (as Mexico was then known to the Spaniards). Two Spanish expert horsewomen, sisters of a captain in Cortés’ military, were members of that voyage; they and their Black maids would fight alongside the men in Tenochtitlan, Moctezuma’s capital, now Mexico City.

But the enslaved Black people who landed with Cortés in 1519 were not the only Blacks from the conquest to be erased from history. Although it is believed that a number of free Black conquerors fought in the conquest of Mexico, only the story of the free Black Spaniard Juan Garrido is known. Garrido was born in West Africa, probably in the Senegambia region to a wealthy family, and went to Portugal around 1494 as a free man, never having been enslaved. Garrido made his way to Seville, Spain, from where, in 1503, he went on an expedition to Hispaniola with Nicolás Ovando, the new governor, who was Cortés’s cousin and whom Cortés would join in 1504. Garrido fought in assaults, which the conquerors called “pacifications” against the Tainos, the native people.

In 1508, Garrido was a member of Juan Ponce de Leon’s conquest of Puerto Rico. In 1510, Cortés and Garrido participated in the conquest of Cuba. Garrido then joined Ponce de Leon’s 1511 exploratory voyage to Florida. When Ponce de Leon and his expedition, which again included Garrido, tried to conquer Florida in 1521, however, the native people killed or wounded a significant number of Spaniards, forcing the expedition to flee to safety in Cuba, where Ponce de Leon died of his injuries.

From Cuba, Ponce de Leon’s men, including Garrido, decided to sail his ship, which was fully equipped with weapons, ammunition, and other supplies, to join Cortés in the Yucatan. They landed at the base Cortés had founded, Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, built by Black and native enslaved people, and marched to his new base, Segura de la Frontera. Cortés was there planning his second invasion of Tenochtitlan, having been beaten and forced to flee by the native Mexicans on his first attempt to conquer the Mexican empire in 1519-1520.

The war for the Mexican empire ended in August 1522; the conquerors beat the natives on their second try, but in the process wrecked the formerly splendid Tenochtitlan. After the war, Cortés imported a significant number of enslaved Black people to work at his new properties, many in Oaxaca, primarily in farms, sugar plantations, silver mines, and cattle breeding. It is no surprise that, today, two of the three largest Black populations in Mexico are in the state of Veracruz (which Blacks helped to build) and Oaxaca, where Cortés enslaved a substantial number of them.

After the conquest, Cortés amply rewarded Garrido for fighting admirably with a position as one of the people who oversaw the reconstruction of Mexico City; Garrido was in charge of repairing the magnificent aqueduct at Chapultepec. Cortés also gave him valuable land and native and Black enslaved people. Garrido would become the first person to plant wheat in Mexico. In 1533, Garrido joined Cortés on an expedition to explore what they believed was an island rich in gold, but they found no such wealth. The conquerors named it California.

Blacks made some of the most important contributions to Mexico. Few know that, in 1829, Vicente Guerrero, a Black native, was Mexico’s second president and abolished slavery. In 1810, during the war for independence from Spain, Guerrero had enlisted in the rebel army and would become its commander-in-chief. After the war, he at first refused to sign a civil rights plan because it did not include equal rights for Black Mexicans.

He also called for liberal programs, including public education, land grant reforms, and equal rights for the economically oppressed. Guerrero is called the father of Mexican agrarianism, which was the rallying cry of the Black and native Emiliano Zapata, leader of the Mexican social revolution of 1910.

When he became president, Guerrero helped write the constitution, the basis for today’s constitution. Conservatives, who opposed Guerrero’s liberalism, forced him out of office in 1829 and assassinated him in 1831. The Mexican state Guerrero was named after him.

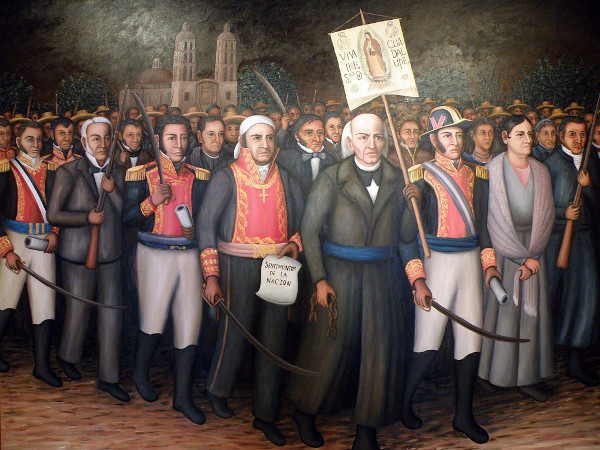

Another Black native, General José María Morelos, who was a priest, beat the Spaniards in 20 battles at the start of the war for independence. Morelos, like Guerrero, advocated for equal rights of the races and for an end to slavery. In 1815, Spaniards captured and executed Morelos. Today, a Mexican state is named after Morelos and Mexico’s 50-peso bill bears his image.

Author Bio:

Marlen Supaya Bodden is a lawyer; author; and anti-war, anti-slavery, and anti-death penalty activist. She drew on her knowledge of modern and historical human rights abuses to write her forthcoming historical fiction Arrows of Fire, which is about the European conquest of Mexico.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

Anacleto Escutia (painting from 1850 – Wikipedia, Creative Commons)

Mexican Independence painting (Eduardo Francisco Vasquez – Flickr, Creative Commons)

Jose Maria Marelos painting, circa 1812 (Wikipedia, Creative Commons)

Manuel Gonzalez de la Parra ( including cover photo -- Wikipedia, Creative Commons)