Literary Flashback: ‘20,000 Years in Sing Sing’ by Lewis Lawes

The Green Mile, The Shawshank Redemption, The Longest Yard, Oz, Prison Break, Let's Go to Prison, Lockup, Locked up Abroad, Jail, Superjail, American History X, Cool Hand Luke, Human Centipede 3: Final Sequence, The New Kid: all these movies and television programs, and this isn't an exhaustive list, find significant portions of their plot or focus on time served behind bars. Alongside brief interludes where characters spend time incarcerated, this proliferation of prison settings and references, but more importantly the eyes turned towards them, indicate reason to say that the American viewer is fascinated with penal institutions and has been long before thousands of people gathered in arenas to chant “lock her up.”

For a country fixated on law and order, where police procedurals, courtroom dramas, Judge Judy and Cops crowd the television airwaves, and many a local paper keeps a police blotter proudly proclaiming the latest arrests and announcing the latest misdeeds, it seems natural that the final stages of this process would be of some interest to the public. So in America of 2016, as in the America of the 1920s and 1930s, when mass media and prohibition catapulted the likes of Al Capone into living rooms across the country via newspapers and radio.

Despite the fame of the various Machine Gun Kellys, Bonnies and Clydes, and Bugs Morans, it was also a time when the lawman was, by virtue of the renown of his quarry, similarly exalted. J. Edgar Hoover, Frank Hamer, and later on Elliot Ness, the FBI's “G-Men,” obtained a similar glamorization. Yet long after the thrill of the police chases subsided, after the ambushes, shootouts and courtroom pyrotechnics, there lay another task — that of the carceral institutions. While many Americas can tell you the name of a famous criminal, and some may even mention a famous law officer or prosecutor of some renown, conspicuous by their absence from the public imagination in any positive light are the men and women whom we've charged with reforming the felon, the social workers and all too often the corrections officers. Due to this state of affairs, it seems unlikely the average American would be able to name more than the most local institution in America's penal archipelago.

Today, the most famous penal institutions are probably Guantanamo Bay; Alcatraz, California's San Quentin and Folsom Prisons, and Arizona's Maricopa County Jail. In the case of the first, the inmates and prison practices catapulted a facility that, prior to 9/11, was an unknown outpost of the American imperium. In the case of the second, the prisoners, including the “bird man” of Alcatraz and Al Capone, made the prison famous alongside its location, in the middle of the shark-infested, eddying waters of the San Francisco Bay. In the case of the third two, popular culture references have made them famous. And, in the last case, we see prison practices — like antiquated striped apparel and chain gangs, which though old are conspicuous by their perceived abolition; and pink undergarments — that are catnip to a people clamoring not just for the felon's apprehension and conviction, but also his punishment and humiliation. Alongside these practices, rather behind them, we see a man who's likely America's most famous local official, Sheriff Joe Arpaio, who made the changes and statements which made him and his prison the cynosure of the nation's tabloid-conditioned eyes.

Aside from this notable elected example, it seems most prison officials avoid the limelight — even as the fame of their institution and their wards eclipse their own. On the whole, this might be for the best, as grandstanding isn't always associated with good or effective policy decisions. For example, despite recent drops, “America's Toughest Sheriff,” Arpaio, must still contend with a crime rate slightly above the national average (using the last available statistics). But, in general, this avoidance tells us little of what prisons are like, how they work, and how they can be improved. While society fixates on Sheriff Joe's quixotic scrutiny of presidential birth certificates and argues about whatever his latest outrage against what passes for decency, the mechanics of recidivism, how it declines, and what it means regarding the laws we're supposed to contribute in making — through electing and holding accountable legislators — remains as mysterious most as Old Slavonic.

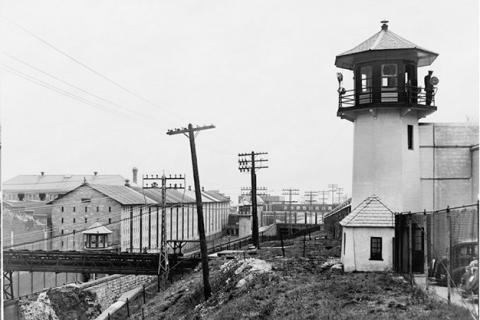

Things weren't always this way. A brief view to the past reveals a different sort of public official. From 1921 until 1941, New York State's Sing Sing correctional facility was presided over by one such official, the fittingly named Lewis E. Lawes. In a career that started in 1905 at Clinton Prison in Dannemora, New York, Lawes saw much of the New York State prison system, serving at Clinton, Auburn, and Elmira before becoming superintendent at the Hart Island Reformatory; in 1918, Lawes took on his first warden position at Massachusetts State Prison. Finally, in 1920, Governor Al Smith, one of the better products of the Tammany Hall machine, appointed Lawes to be the warden of Sing Sing, a position Lawes would hold until his retirement in 1941.

During this long public career, he remains Sing Sing's longest-serving warden, one can conclude that if it's anything Lawes had experienced, it was prison life. It was a modus vivendi Lawes knew well enough to write about, and, perhaps as a function of the aforementioned public appetite, Lawes was not only published twice but adapted for the silver screen. An examination of his twice-adapted nonfiction book, Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing, will do much to illuminate the thinking of this exemplary official.

While most see it as a terminal point, in life and a prison stay, Lawes begins Twenty Thousand Years with a tale he'd known all too well: “I have been directed to kill lawfully one hundred and fifty men and one woman.” The adverb splits the sentence, giving it a measured, even tired tonal quality. But the most moving passage of the prologue is not a statement of the author's belief, “My experience has convinced me of the futility of capital punishment,” but instead his account of a young boy's reaction to the radioed spectacle: “The door of a bedroom of an apartment on the third floor closes softly. Young Ted climbs quietly into his bed. Ted is fifteen. An impressionable youngster. He has been ordered to bed an hour ago, but he hadn't missed a word of that broadcast through the slit of the partly opened door. Now he is lying back on his pillow, his eyes staring into the darkness. His mind reviews the story. 'Gee, but he was a brave fellow, all right.'” It's a lot different than Angels with Dirty Faces and perhaps Ted is a little past the age of impressionability, but conceptually Lawes notices something about the glamorization of the criminal through description of the deed and the punishment, which takes on ritualistic vestment when publicly broadcast.

Aside from ruminations on the ineffectiveness, brutality, and mendacity — with jurors first condemning a man, then later, unanimously signing petitions for sentence commutations — of the death penalty, Lawes provides episodes from many a life lived behind bars. Truly there's something for everyone here. We learn of Mike, the rat catcher, and Charles Chapin, the newspaperman turned “Rose Man” of Sing Sing. Lawes' description of the “Rose Man” is equally flowery: “He removed Sing Sing's raiment of sack-cloth and ashes — traditional in all prisons — and draped it with a mantle of green verdure and fertility. Its freshness and beauty are symbolic of the purposes we hope to achieve among the men entrusted to our care; to infuse new life in the debris of human backwash that eddies with endless flow through the gates of the prison.” By similar devices, Lawes frequently moves from the stories of hopeful individuals to the goals of prisons as institutions.

Lawes shows us not only the issues we still see in many prisons today (see this New York Times article). The prevalence of so-called “prison families,” where generations of the same family have worked at the local prison; problems with the prison labor system; problems adjusting to life on the outside; three strike laws (the Baumes Laws); and, of course, the perpetual dilemma of a public uninterested in matters of law until, of course, it starts hitting close to home. All these are featured in the article, and, coincidentally, Sing Sing is the bright spot in the New York State prison system; Lawes and his efforts, however, remain unmentioned.

It's probable that this is because as a historical figure Lawes represents somewhat of a difficult pill to swallow. A public official who carried out his duties even when he vehemently disagreed with the policy behind them, as with the Baumes Laws and capital punishment, and wasn't afraid to go to press to say so. In a time where more and more issues become tied to the push and pull of partisan politics, any such official runs the risk of both making enemies and alienating his benefactors.

If American prison and legal reform are to go anywhere, knowing what we've done in the past is as good a place as any to start. While Lawes may seem to be dated — Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing has been, to the best of my knowledge, out of print for years — bringing him back into the conversation is, at this point, a necessity. Efforts have been made in the past, in the New York Times “City Room” blog, Ralph Blumenthal described the rise and fall of Warden Lawes.

Perhaps of all the books I've found at yard sales, this would be the most enlightening. Lawes goes to great strains to show the humanity of criminals, a trait often disregarded in the face of their crimes and, indirectly, what it means to be a public servant. There are even a few cringe-worthy passages about escapes that will leave the reader both on edge and amused. We can safely regard this as one of the tragedies of modern publishing that this book is out of print.

Author Bio:

Adam Gravano is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine