How a 1920 Wall Street Bombing Tanked the Career of a Famous Detective

“There are about 25 dead and about 200 hurt and some are very badly hurt,” Charles Scully, head of the Bureau of Investigation (BI) Radical Division in New York, wrote in a memorandum during the evening of September 16, 1920. The BI was the forerunner of the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI), and they were tasked with investigating the bombing that a few hours earlier had rocked Wall Street, sending the city into a frenzy. Scully was right about the number injured but wrong about the number dead. The death toll would eventually rise to 38.

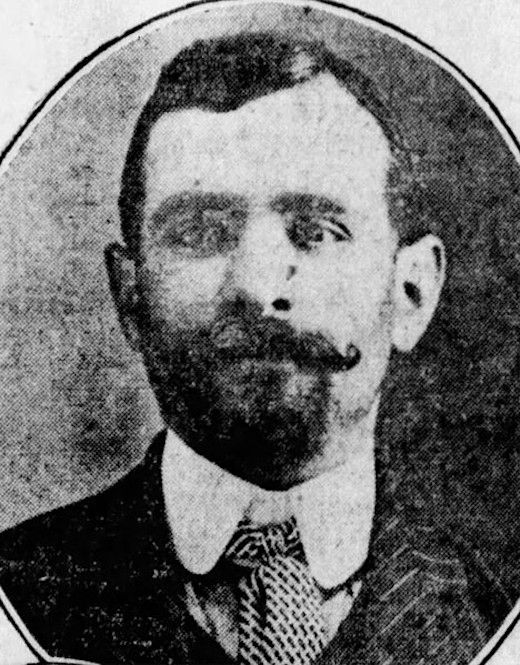

William J. Flynn was in Washington when word reached him about the bombing. Flynn was a celebrated law enforcement official known as the “Bulldog Detective,” for his tenacity in investigating and solving crimes that stymied other law enforcement personnel. He had been named director of the BI in 1919. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer immediately put him in charge of the federal investigation, which involved about 5,000 government detectives connected to the Department of Justice, Treasury Department, Post Office, and Bureau of Immigration.

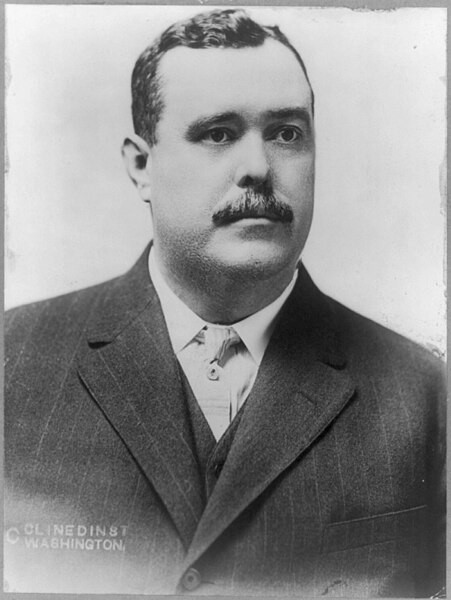

Of all the different investigators that would become involved in the case, there was one that Flynn knew would make life hard for him. William J. Burns was as famous as Flynn, if not more so. The two men didn’t like each other, even though they had much in common. They were both Irish and stubborn and loved media attention. They willingly granted interviews to reporters, wrote stories about their exploits, and delved into the movie business. They also even worked together for a brief time at the Secret Service. But whereas Flynn was more concerned with serving his country in government positions than making money in the private sector, Burns was the opposite. He had an entrepreneurial spirit and became a confidante of the rich and powerful. And while Flynn was never tainted by any type of scandal, Burns, who was six years older, dealt with scandals throughout his career.

In 1909, Burns established his own private detective agency. The height of his fame came in 1911 when he identified the culprits behind a bomb attack at the Los Angeles Times building a year before. The bombing generated headlines across the country. It was the worst act of domestic terrorism at that time, only to be surpassed 10 years later by the Wall Street bombing.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing for Burns following his success with that case. In 1916, he almost lost his New York State private detective license after being found guilty of wiretapping the offices of a legal firm on behalf of one of his clients, J. P. Morgan and Company. He was fined $100, but his conviction was reversed on appeal.

By the time of the Wall Street bombing, though, Burns had lost a lot of his luster. He needed it to get back in the limelight and generate the praise and acclaim that he had grown accustomed to. Investigating the bombing could also mean more lucrative contracts for his private detective agency.

As is often true when there are multiple witnesses to a crime, there were varying accounts of the explosion. A sample of 21 witnesses did, however, reveal some points of agreement. Most of them said that a horse-drawn wagon was parked in front of or near the U.S. Assay Office, which was located on Wall Street at the time, and that it was old and dilapidated, its paint worn off. The color of the body of the wagon was dark or dirty gray, while the wheels were dark red. The horse, a dark bay, was aged, thin, and in poor condition, its front knees badly sprung. The witnesses could not, however, provide sufficient information about the most important clue the investigators were after: a description of the driver.32

Investigators had already checked out the businesses that the victims of the bombing were involved with and were able to determine that none of them owned or operated the horse-drawn wagon that exploded. That meant that whoever set off the bomb had gotten away. Flynn was optimistic that the perpetrators would be found. “We’ll get them,” he told the press. From the start, he was convinced that it was the Galleanists who were behind the attack. The Galleanists were a radical anarchist sect, founded by Luigi Gealleani, an Italian national who took up residence in the U.S., and was later deported in the Palmer Raids.

Flynn was under enormous pressure to solve the case. The New York Chamber of Commerce labeled the bombing an “act of war.” The New York Times wrote in an editorial that the perpetrators “will be hunted down in their lairs like wild animals. Every device and stratagem of detection will be put in operation against them.” Newspapers across the country reported daily on the progress (or lack of it) in the investigations. Expectations were high that Flynn would be the right man for the job. “Chief William Flynn, the famous ‘Big Bill’ hurried to New York to assume personally the task of the unraveling of the mystery,” the Los Angeles Times reported. Another newspaper ran a story about the bombing under the heading “William J. Flynn Will Run Down Conspirators.” And the New York Daily News wrote, “William J. Flynn, chief of the Bureau of Investigation of the Department of Justice—big, fat, friendly, conservative and yet generous with information (‘a whale of a man’ . . . )—will within twenty-four hours, it is believed, hold in the toil of the law those responsible for the Wall street disaster.”

Investigators could not determine exactly how long the wagon was parked in the street before the explosion. One witness said he saw a delivery wagon driving toward the Assay Office about one minute before the explosion occurred. Flynn believed the driver abandoned the wagon on Wall Street after setting the timer for the bomb a few minutes ahead. Another witness, however, said he saw a wagon parked unattended outside the Assay Office for at least an hour. If true, then it meant an old, beat-up wagon with a sickly-looking horse had been parked in the heart of Wall Street without arousing suspicion about its presence there. The Wall Street Journal criticized city officials for not policing the Financial District, which might have prevented the attack.

Since the horse suspected of drawing the bomb-laden wagon to Wall Street had been killed, investigators set out to determine whether any stables were missing a horse, either one that had been stolen or one that was never returned after being used on September 16.

Photostat copies were also made of two horseshoes with specific markings that were found outside Trinity Church near the bomb site. These were shown to approximately 4,000 blacksmiths along the Eastern Seaboard. One of them, Gaetano DeGrazio, whose shop was in the Little Italy section of Manhattan, recognized them and told agents he had made the shoes and shod the horse the day before the bombing for a man he described as Sicilian. Flynn arranged for DeGrazio to view hundreds of photos of anarchists with the hope that he might be able to identify his customer. To make sure, however, that DeGrazio wasn’t in some way connected to the bombing, Flynn had a BI confidential informant, code name “P-137,” watch his shop in case any suspicious people visited or in the eventuality that DeGrazio tried to get in touch with anybody who could be of interest to the bureau. The informant reported that he observed nothing of importance during his surveillances.

While DeGrazio was viewing the photographs, investigators were busy on many different fronts. One involved trying to locate the person or persons who had bought a set of rubber letter stamps that were used to make propaganda leaflets found in a mailbox (without any envelopes or addresses) just a few blocks from Broad and Wall streets on the day of the explosion. These leaflets, which Flynn described as “a challenge to the American Government,” were similar in message to those that were discovered at all the sites of earlier bombings tied to anarchists. Rubber-stamped in red ink on white paper, the Wall Street leaflets warned of additional attacks: “Remember, we will not tolerate any longer. Free the political prisoners, or it will be sure death for all of you.” They were signed “American Anarchist Fighters.” This signature convinced Flynn that the same group of Italian anarchists (the Galleanists) had composed both sets of leaflets. “You can see,” he said, “they have simply added American to their title now.” (The flyers found at the sites of previous bombings were signed “The Anarchist Fighters.”) “The similarity of the circulars makes available all our knowledge of the gang who committed the outrages last year,” Flynn also said.

Investigators learned that the R. H. Manufacturing Company of Springfield, Massachusetts, had produced the set of rubber stamps used to create the leaflets. This discovery was made because the word “for” in the leaflet (“death for all of you”) had a distinct style found only in “The Easy Sign Maker #0” rubber letter set that the company manufactured. More than 2,000 retail stores were visited by agents in the New York area to see to whom they might have sold such sets. No results were obtained from this part of the investigation. The same was true for stores visited in other cities throughout the East and Midwest.

As the weeks and months passed by with no progress in the investigation, Flynn decided on a long shot. He would send one of his informants undercover to Italy to try to track down Luigi Galleani and elicit information from him about the bombing. This was ironic, of course, because had the government not deported Galleani in 1919 in the infamous Palmer Raids, they wouldn’t have had to look for him overseas.

The task of finding Galleani fell to Salvatore Clemente, a former counterfeiter turned police operative whom Flynn had worked with in the past. Clemente, posing as an anarchist from Paterson, New Jersey, was given the code name “Mull” and set sail for Italy, his home country, at the end of December 1920. When he arrived in Rome, an American diplomat gave him photos of Galleani and other Italian anarchists. He then went to Milan and met up with a Galleanist he knew from America, Antonio Mazzini. Mazzini informed Clemente that Galleani was nowhere to be found in Italy, having fled the country to avoid arrest by the Italian authorities after resuming the printing of his newspaper, Cronaca Sovversiva, in Turin. Clemente was able to locate Galleani’s sister Carolina in Vercelli, who also told him that her brother “had to leave the country.” Having not achieved his mission, a disappointed Clemente returned to the United States in March 1921.

By that time, Flynn was feeling increased pressure for not yet solving the Wall Street bombing. Many people wondered if it would ever be solved. And there were media reports that Flynn would soon be replaced as director of the BI by none other than William Burns. A new president had taken office, and he appointed a new attorney general, and neither of those developments boded well for Flynn.

Flynn, meanwhile, was working on what he hoped would be the big break in the case. Early in January, he began circulating to chiefs of police and postmasters in Eastern cities a composite drawing of who he suspected was the driver of the horse-drawn wagon that exploded on Wall Street. Gaetano DeGrazio, the blacksmith who shod the horse’s shoes, identified two photographs from the hundreds of anarchists he was shown, claiming they somewhat resembled the driver who brought the horse to his shop. It was, however, as historian Beverly Gage points out, only “educated guesswork.”

DeGrazio worked with a commercial artist combining the two photos to make a composite drawing, suggesting changes to various features along the way. The wash drawings were then photographed and circulated to the select audience. Included with the photograph was a physical description of the driver as being “apparently Italian, 28 or 30 years; 5 feet 6 inches; medium build; broad shoulders; dark hair; dark complexion; small dark mustache, which at the date of the explosion represented about two weeks’ growth. He wore a gold cap, pulled down over his forehead, and khaki shirt turned in at the neck, as indicated in photograph.” The communication to the police chiefs and postmasters was supposed to be confidential, but the New York Herald got hold of one and published it on March 31. Other newspapers then reported on the story. “I have no knowledge as to how or where the newspaper obtained the circular and photograph,” Flynn wrote in a memo to Harry M. Daugherty, the new Attorney General, in April.

Flynn informed Daugherty that he had received many replies regarding the circular he sent out (he did not mention whether any information came from the newspaper publishing the material) and that all of the replies “have been or are under investigation.” One of the leads involved a person named Vincenzo Leggio, but the bureau soon learned that Leggio had moved to Italy in the spring of 1920. There were no reports that he had ever returned. But when police in Scranton, Pennsylvania, arrested an Italian anarchist named Tito Ligi for draft evasion, they found what they said were sash weights identical to the shrapnel used in the Wall Street bomb in the back room of a restaurant where Ligi once worked. Flynn now thought that he had finally gotten his man, given the similarity in the last names, and that Ligi was actually Vincenzo Leggio.

Even though the so-called sash weights turned out to be irregular blocks of iron and steel that Italians in the city used for playing a game, Flynn still summoned to the BI offices in New York a number of people who had previously stated that they had seen the driver of the bomb-laden wagon. These witnesses were shown 25 photos, Ligi among them. Two of the witnesses (Thomas Smith, a former New York Fire Department lieutenant, and James Nally, a stockbroker’s clerk) picked out Ligi’s photo “as that of a man closely resembling the driver.” But when the photograph was shown to DeGrazio, the blacksmith, he said Ligi was not the man who came to his shop the day before the bombing. Nevertheless, Flynn arranged for Smith and Nally, as well as a few other witnesses, to travel to Scranton to identify Ligi in a police lineup.

Only Smith was able to make the identification. The other witnesses did not recognize Ligi. Smith, however, now claimed that Ligi was not the driver of the wagon but rather a person he saw talking to the actual driver about a half-hour before the explosion. New York police detectives had little faith in Smith’s account, claiming he was nowhere near Wall Street at that time on September 16. The case against Ligi soon fell apart, with Flynn admitting publicly that the BI had no evidence connecting Ligi to the bombing. But Ligi was still sentenced to one year in prison for draft evasion.

By now, Flynn was like a boxer, far behind in points going into the last round against his opponent. Only a knockout would win the bout for him. With Burns waiting in the wings, Flynn likely knew he needed to solve the case soon to keep his job. Especially since the current Attorney General Daugherty was an old friend of his nemesis, William Burns. His last hope came around the same time that Ligi went to prison. A man named Giuseppe De Filippis was arrested in early May in Bayonne, New Jersey, because of his alleged resemblance to the composite drawing of the wagon driver. Witnesses were once again brought in, this time to the Bayonne jail, to identify him as the driver. Once again, inexplicably, Smith was among the witnesses. He now identified De Filippis as the driver, as did two other witnesses. But once again, the case fell apart, as there was no other evidence against De Filippis, who was not an anarchist. He claimed that he was at a Bayonne railroad siding on September 16, hoping to be hired to haul California grapes that were being unloaded there from a refrigerated car. Several witnesses confirmed his story.

Flynn remained in his job for most of the summer. But the ax fell on August 18, when Daugherty announced that Burns would be the new BI director. He told reporters that Flynn had not yet resigned but that he had been notified of Burns’s appointment. Daugherty had sent Flynn a telegram to his New York office informing him of the decision while Flynn was on vacation in Saratoga.

Burns held onto his job for few more years but was eventually forced out in May 1924 after a major scandal involving spying on a U.S. senator. Burns had used BI agents to try to gather evidence of criminal activity on the part of Senator Burton K. Wheeler from Montana after the senator called for Congress to investigate abuses in the Justice Department. Attorney General Daugherty was also forced to resign for his involvement in the scandal.

The last time the FBI looked into the bombing was in 1944, and once again, no results were obtained. In a summarizing memo to headquarters that year, the New York office repeated the contention made just a month after the attack by Agent Scully—namely, that “Italian Anarchists or Italian Terrorists” were responsible for the bombing.

Adapted from The Bulldog Detective: William J. Flynn and America’s First War Against the Mafia, Spies, and Terrorists (Prometheus) by Jeffrey D. Simon. Published with permission.

Author Bio:

Jeffrey D. Simon is an internationally recognized author, lecturer, and consultant on terrorism and political violence.

Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Depositphotos.com; Wikimedia Commons; George Grantham Bain Collection (Wikimedia Commons); Library of Congress (Wikimedia Commons); Wikipedia Commons; Archives New Zealand (Flickr, Creative Commons).