Martin Amis Amongst the Thugs: The World of ‘Lionel Asbo’

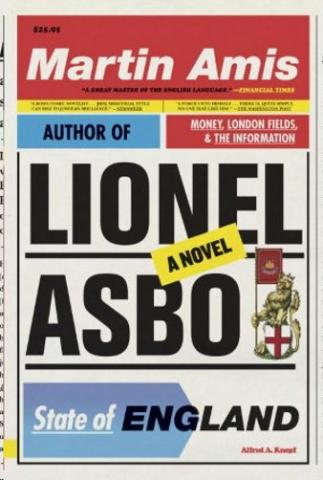

Lionel Asbo: State of England

By Martin Amis

Knopf, 255 pages

What living novelist brings more baggage to the publication of a new book than Martin Amis? Each occasion triggers a recounting of wildly irrelevant details from his past (no need to repeat them here), generating a media frenzy to which Amis often contributes with outspoken views on culture, politics and history. By now (Lionel Asbo is his 13th novel), this frenzy serves not to enlighten but to distract from the work itself. In that respect, Amis remains one of the most consistently interesting and—on a purely sentence-by-sentence level—one of the best writers we have.

The plot, such as it is, revolves around the relationship between the title character (a London street thug who’s changed his last name to an acronym for Anti-Social Behavior Order) and his mixed-race nephew Des Pepperdine. Des and Lionel reside in a council flat in the fictional neighborhood of Diston, “with its burping, magmatic canal, its fizzy low-rise pylons, its buzzing waste.” Lionel’s money-making endeavors are strictly criminal, while his teenage nephew aims for a more conventional station in life. The problem is, as the novel opens, he’s having an affair with his 39-year-old grandmother—a secret that must be kept from “Uncle Li,” since the consequences of discovery are beyond imagining.

Lionel’s life is transformed upon winning £140 million ($220 million) and becoming, in the British press, the “Lottery Lout.” This king’s ransom makes possible the purchase of a manor house and a small army of public relations advisers and security agents. Yet for the eternally dissatisfied and pathologically self-absorbed Lionel Asbo, somehow it’s not enough:

“All the same he felt light, light, insubstantial, hardly there. Every time he went to the casino and the lift came to a halt on the penthouse floor, Lionel expected to keep on surging upward, past the helipad and the Century City Eyrie and out into the summer blue … The weightless world, the light limbo, of the South Central, where nothing weighed, nothing counted, and everything was allowed.”

Lionel’s new wealth will enable him to exact a terrifying revenge on his nephew for his incestuous behavior many years ago.

But plot isn’t the reason to read Martin Amis. Language is his true dominion, a manic, bubbling and light-footed style that depends as much on the reader’s ability to keep up as on its own hard-earned effects. From Money and The Information to the unjustly maligned Yellow Dog, his prose remains concise, lyrical and over-reaching, all at once. Take, for example, this description of just one part of Lionel’s immense baronial estate:

“The village nestled on a rise over a shallow valley, and Lionel’s vast garden was arranged on three levels, three graded distances, eventually subsiding into a pasture of paler green where two tiny horses nuzzled and browsed. The uppermost lawn was tyrannized by a sky-filling cedar, caught in mid-flail, ancient, grand, and haggard, and half-supported, now, by tripods made from its own wood. Dropped branches, fashioned into crutches.”

As everywhere in Amis’s work, some of the linguistic special effects resonate and some don’t. Dogs are “missiles of muscle” and a restaurant owner has “an icecap of thick white hair.” On the other hand, a high-rise “loomed like a whimsical robot over the stubby bohemia of north Pimlico.” Surrendering to the pleasure of his prose means abandoning orthodox notions of the “proper” use of metaphor and simile.

There are pleasures as well in Lionel Asbo’s voice. By and large, American readers won’t know if the speech patterns are authentically idiomatic, but that’s beside the point. There’s a delightful poetry to his unfettered, consistently vulgar manner of speaking—as when he waxes nostalgic about taking in his orphaned nephew: “Gaa, the state you were in when I come to you rescue. Crying youself to sleep at night. You was … you were always brushing up against me for a hug, like a cat. And I’d say, Get off, you little fairy. Get off, you little poof. I’d say, If you want to ponce a cuddle you can go round you gran’s. But now you doing all right.”

Or when expostulating about the mysteries of the female of the species:

“Sunday morning. I’m lying there Sunday morning. I’d just had this dream about Gina Drago. And she was all dark and uh, glowing. Beautiful. Then I open my eyes and what do I see? Cynthia. Like a dairy product. Like a f***ing yoghurt. And she says, What’s the matter with you? You had a nightmare? And I say, No, love. It’s just me guts acting up. Because they all got feelings, haven’t they, Des. All got feelings. God bless them.”

The universe of Lionel Asbo bears a passing resemblance to the one we inhabit, but life moves at a faster clip and violence of all kinds (though particularly towards angelic infants) is always possible. Readers turned off by prose that calls attention to itself should choose another book off the shelf. For the rest of us, Martin Amis is an international treasure.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, Highbrow Magazine's chief book critic, is the author of a novel, The Moon in Deep Winter.

Photos: Courtesy of Knopf and Barnes and Noble.