Jennifer Lopez and Spanish Linguistics in the Age of Black Lives Matter

Just about a year ago, global superstar Jennifer Lopez released two songs in tangent featuring Colombian singer Maluma. The songs, collectively referred to as Pa’ Ti + Lonely, are part of the soundtrack for the two celebs’ upcoming film Marry Me, due for release next year. The song Lonely contains a line that Lopez dialogues in Spanish: Yo siempre seré tu negrita del Bronx. It created a bit of firestorm in an already stuffy and heated racial climate, fueled by the conversations around racial justice, immigration, and identity that were already taking center stage.

For good reasons, too. The criticism against the lyrics were valid in many ways; and I say in many ways because some of it was, of course, just hateful for the sake of getting to tweet about it. It all centers on the perceived meaning of the word negrita within this context, “perceived” being the key word. Literally, the word translates as “little Black girl.” In other words, in a literal translation, what Lopez sings is: “I will always be your little Black girl from the Bronx.” The initial backlash was swift for obvious reasons. It’s worth mentioning that it seems that those who first began calling Lopez out were other Latine people from the United States, who with even the most basic knowledge of Spanish, were able to quickly translate into English what the singer said.

But many also immediately came to Lopez’s defense, explaining that the word negrita doesn’t actually mean “little Black girl” in Spanish, but rather it is a word of endearment that would more accurately be translated as “honey” or “sweetheart.” Now, this is factually true. There were some who mentioned that negrita is a term of endearment for any light-skinned Black girls. But at least in Puerto Rico (where Lopez has roots) and in South America (where Maluma is from), the word negrita is a term of endearment used arbitrarily for any and every girl. The palest, blue-eyed blonde would be called negrita because within this cultural context, it just means “honey.”

But the root of the word negrita by its own merit is racialized, and that’s also factually true. While contextually the word may be a term of endearment in modern use, its origin is still one mired in racist history, colonialism, and colorism; especially because the tone, social standing, and cultural context all play an important facet in how the word is perceived. And this truth is what sparked the biggest conversation around Latinidad, the anti-Black racism that is still prevalent in Latin America, and even who gets to “claim” Latinidad within the American framework.

Latinidad can be loosely translated as “Latin-ness.” It’s a term that’s been around since the mid-1980s as a way to speak about Latine communities specifically outside of Latin America, especially within the U.S. It’s an umbrella term of sorts, meant to facilitate the conversation about Latine peoples, culture, language, belief systems, etc. as they are practiced in the U.S. But as any umbrella term, it has its limitation. Because Latinidad is generally viewed within its American context, it’s oftentimes exclusionary because of the limited outlook that America itself has of Latine people.

In other words, because Latinidad seeks to create a unified Latine experience in the U.S, it undoubtedly ends up painting a monolithic view of what it’s supposed to be like being Latine in America. It inevitable gets corrupted to fit the American narrative; in fact, more modern uses of the word opt for Latinidades to try to cover the plurality of Latine peoples. And to be sure, there are myriad commonalities and shared experiences in being Latine in the US; but because Latinidad is framed within the American experiment, it brings with it the racial connotations that are inescapable in the U.S. along with Latin America’s own ugly racial history. And so Latinidad comes to mean that you’re a hard worker, you have an immigrant story, you have strong family values, your Spanglish is smooth and fluid, you call your mother every Saturday and go to church on Sundays, and you have that idolized Latine look of Ricky Martin or of, yes, Jennifer Lopez.

That’s why it’s important to talk about Latinidad when we talk about Lopez’s negrita affair and the intersections of discrimination against minority groups. Because, for once and for better or worse, Lopez does have that romanticized Latine woman look – the straight long auburn hair, the always perfectly-sun-kissed skin tone that’s not too light but definitely not too dark either. We do have to tread carefully and be fair here, because the point is that there isn’t a “perfect” Latine look, and that Lopez embodies what we epitomize as the model Latine face and body speaks more to our culture and society at large than anything else. But because nothing exists in a vacuum, this is irrevocably part of the issue, or at least it informs some of the backlash that the lyrics generated. Lopez has never identified as Black, using this term so blatantly caused some anger, be it for the apparent clout to use an identity that was “in vogue” or because of Lopez’s historied misuse of Black culture. And while the meaning of the word negrita within this cultural context is relevant, it too is relevant to the actual roots and real definition of the word.

Slavery and racism in Latin America has a long history, and its remnants are still everywhere and very visible, just as they are here in the U.S. It’s no secret that anti-blackness and anti-indigenous racism still exists in Latin America and within the Hispanic populations at large, hard as we may try to sweep it all under the rug of brownish skin tones.

So the word negrita will always inevitably retain some of its original racial connotations because we just don’t live in a post-racial world, and the semantics do matter. There is even a curious parallel here because just as some English words that were once slurs have been retaken and rightly appropriated by the Black community, so has the word negro/a taken different nuances in Spanish. At its core, the word negro/a means “Black” and it is an adjective that identifies a race, just as it is in English. But in Spanish, the word is also a noun. Historically, the noun form has been used as a pejorative, used to demean and dehumanize. And while that remains true, the noun has been slowly but surely taken back and repurposed.

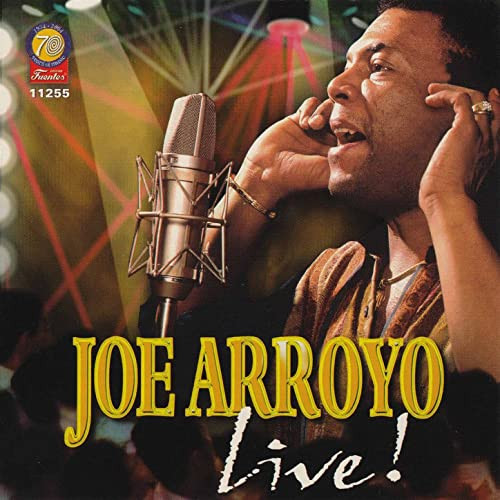

Just go to any Latine house party and Joe Arroyo’s La Rebelión will undoubtedly be played – a salsa by a Black Colombia singer that tells the story set in Cartagena sometime in the 17th century of a Black couple enslaved to a Spaniard who beats her. The song is truly ubiquitous in any Latine household whenever some dancing is involved, and Black Latine have since claimed it as an anthem of Black pride and identify, because this salsa is basically a draft of Django Unchained in song form (in case it wasn’t apparent, the title of the song translates to “The Rebellion). Same story with iconic Cuban singer Celia Cruz’s La Negra Tiene Tumbao, which would loosely translate to “the black woman has swag.”

As exemplified by the above, the ever-shifting nature of language is also an integral part of this matter. As Spanish-speaking immigrants, our language is one of the purest vestiges of our culture that we get to keep (when it’s not being policed). So I must admit that when I first heard of this issue, my initial knee-jerk reaction was to say, “But that’s not what it means! Y’all must be English-speaking Latine because you obviously don’t know Spanish that well!” And immediately after that, I thought, “Wait… so are they not “allowed” to call it out? Are they Latine enough or is that not even a thing?”

It’s not a thing.

But it’s worth mentioning because Lopez’s own Latinidad has been questioned before – as far back as when she played beloved late singer Selena. Lopez has been widely criticized for not speaking Spanish well enough. She may be Puerto Rican and claims those roots proudly, but she was born in New York after all, so her first language is English.

To what extent, then, can she claim the language and specially to use it within the deep cultural context in which the word negrita lives? I don’t know that there’s a specific barometer here or even if there should be one. Likewise, Christina Aguilera has not actively distanced herself from her Latine roots, but that didn’t stop the criticism when she released a best-selling Spanish album even though she infamously doesn’t speak the language; she even acknowledged that it may not sit well with some people. Aguilera recently returned to singing in Spanish, releasing a feminist-themed guaracha (a Cuban genre of music popular and beloved throughout the Caribbean) where she does sing with a marked accent. That Aguilera is a blue-eyed blonde doesn’t mean she doesn’t get to claim her Latinidad—even her last name is a dead giveaway. And for the record, iconic Mexican-American singer Selena didn’t speak Spanish very well either.

So even if Lopez’s lyrics were not meant to be offensive within the culture of Spanish speakers, it was at least tone deaf. In the music video, she even delivers the line while she’s behind bars in a prison. In the end, it should all be about how we can better protect or unite with the most vulnerable. And it is important to maintain our cultural heritage, especially those that are so ingrained in us and prevailing like our language. But language evolves, as it should. We just have to evolve with it and either do away with some terms or be more mindful of the power that they still yield.

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is Highbrow Magazine’s chief features writer.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Ana Carolina Kley Vita (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--Rafael Amado Deras (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

--DVSRoss (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)

----Anthony Quintano (Flickr, Creative Commons)