Cold War Blunders Abound in ‘Quiet Americans’

The Quiet Americans: Four CIA Spies at the Dawn of the Cold War—A Tragedy

in Three Acts

By Scott Anderson

Doubleday

560 pages

It would be nice to say that the origin story of American clandestine services, starting in World War II as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and later coalescing as the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), resulted in level-headed counterintelligence efforts aimed at promoting democracy throughout the world.

The truth, according to journalist Scott Anderson in his sweeping new book, The Quiet Americans, is anything but.

Anderson focuses on a specific 12-year period (1944-1956), which saw the steady emergence of U.S. intelligence and counterintelligence efforts abroad. In that time, the U.S. government went from saving Western democracy to attempting to destabilize and occasionally overthrow foreign regimes not to our liking.

It’s not a distinguished legacy:

“And at the end of this time span: humiliation. After years of trying to spur an anti-communist uprising somewhere in Eastern Europe, American Cold Warriors were finally handed one in Hungary in October 1956, only to have all their talk of [communist] ‘rollback’ and liberation be exposed as meaningless rhetoric; the image of Soviet tanks rolling through the streets of Budapest to crush the revolution produced great bouts of hand-wringing in Washington, but nothing more.”

Anderson frames his story with in-depth biographies of four CIA operatives largely unheralded in the annals of American espionage. These men include Edward Lansdale, a larger-than-life advertising executive turned secret agent; Peter Sichel, a German Jew who escaped Nazi Germany and later led key operations in postwar Europe; Michael Burke, an ex-naval officer who guided operations in Albania and Eastern Europe; and Frank Wisner, a crusading spymaster who oversaw many covert missions.

This approach mirrors the author’s conviction that the most interesting facet of historical writing emphasizes “people living at the ground zero of events, the stories of those with a direct and personal stake in a drama, rather than of politicians or scholars who experienced it from a higher, safer distance.”

Each of these gifted, ambitious individuals believed strongly in the American way of life. In the 12-year span from the end of World War II to some of the Cold War’s darkest days, their dedication grew out of a virulent anti-communism that sometimes warped even the best of intentions. The historical record is littered with costly international blunders, from botched coup attempts in Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe to behind-the-scenes support of autocratic regimes in Asia and Central America.

Throughout the book, Anderson shares some lesser-known methods of tradecraft. For example, in the last years of military conflict in Europe, Sichel had to secure vast amounts of cash (in the form of French francs) to fund underground commando missions. This entailed working with the black market, where francs were more openly available.

To add credibility to the windfall he collected, Sichel made sure the francs “appeared used” to the eventual recipients:

“From past efforts, OSS special funds officers knew that simply spreading dirt on new money accomplished very little, that the best way to produce the needed scuffing effect was to scatter the bills over a floor and repeatedly walk on them for several weeks … By long tradition, French banks often bundled together higher-denomination notes by running a thin, single-prong ‘staple’ through one corner of the bills. Thus, Sichel and his OSS colleagues were required to painstakingly ‘pinhole’ their mountain of francs before they were ready for circulation.”

Anderson skillfully interweaves the lives and exploits of the four Quiet Americans, so readers should be prepared to swerve from one storyline to another. There’s also a wealth of colorful, espionage-related anecdotes, some more intriguing than others. This, too, puts demands on the reader to closely track all the principal and ancillary personalities, as well as their various underground activities.

On the other hand, the scope of this story requires a broad and detailed canvas. In this respect, Anderson delivers. Readers wishing to learn more about the roots of the CIA, and its decades-long history of black ops, will be rewarded as they wade through these pages.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi, Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic, recently completed a novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash.

For Highbrow Magazine

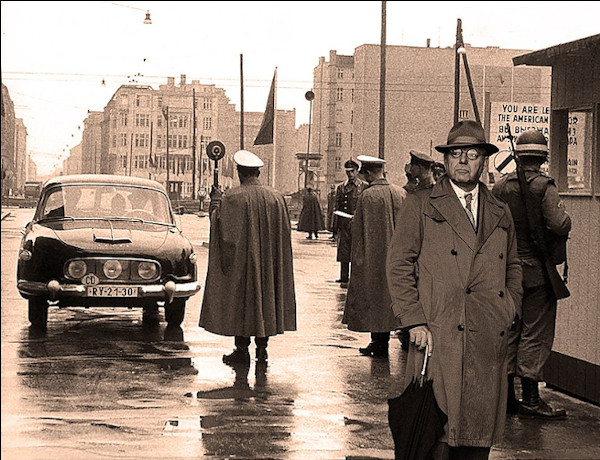

Image Sources:

--Doubleday

--National Museum of the USAF (Creative Commons)

--Jan Saudek (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)