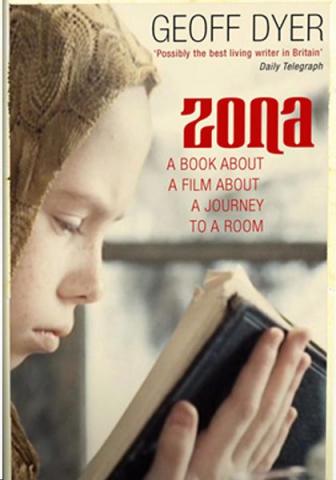

In ‘Zona,’ Geoff Dyer Attempts to Uncover the Mysteries of a Cinematic Masterpiece

Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

Geoff Dyer

Pantheon, 240 pages

Geoff Dyer introduces his book Zona with a phrase attributed to Albert Camus: “Perhaps, after all, the best way of talking about what you love is to speak of it lightly.” Dyer then goes on to write about Andrei Tarkovsky’s intellectually demanding and spiritually compelling film, “Stalker.” Dyer stays true to his epigraph, speaking of this film so lightly, that he glides over the surface and does not enter the movie’s depths. What results is far from an intellectually demanding book; it is like cautiously soaking one’s feet in the pool rather than jumping inside and feeling the full sensation. Dyer spends a large portion of the book summarizing the film frame-by-frame from his own viewpoint, making jokes about it, relating it to his life and desires, and sprinkling in phrases from other authors. In the end, Zona is not so much “a film about a journey into a room,” as a set of tangents about Geoff Dyer's impressions and Geoff Dyer himself.

Some of the most profound moments in this book occur when Dyer quotes others: the voices of W. H. Auden, Roland Barthes, Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, J. M. Coetzee, T.S. Eliot, Gustave Flaubert, William James, Carl Jung, Franz Kafka, Milan Kundera, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke and William Wordsworth all make their way into Zona. Dyer, perhaps inadvertently, grounds a very Russian work into an English way of thinking, and with these quotes reveals parallels to Tarkovsky’s poetic, psychological and philosophical thought in a Western tradition. For example, toward the end of book, Dyer quotes Jung: “People will do anything, no matter how absurd, in order to avoid facing their own souls.” This phrase is quite apt; the film's larger meaning could be seen through its lens. However, in this instance, as in others, Dyer provides the quotation and quickly moves on with more of the film’s synopsis and his own personal digressions. Many of the quotes in Zona are well-chosen, but they too often replace analysis rather than contribute to it.

Reconstructing a film shot-by-shot is unnecessary, especially if what the author says about those shots is digressive rather than analytical. In Zona, Dyer declares, "There are few things I hate more than when someone, in an attempt to persuade me to see a film, starts summarizing it” because doing so has the effect of "destroying any chance of my ever going to see it.” However, he does just that. As he summarizes, Dyer does not try to uncover the complex mysteries of the film and does not manage to infuse the cinematic images into the text; rather, he cheapens them, providing a limited description of a rich sensory experience.

In Zona, Dyer attempts to combine the silly and the intellectual—yet it seems that he adds in facetious comments in fear of sounding scholarly or pretentious. He then always makes his way back to the highbrow to avoid seeming that he is all about the fun.The result is a collection of half measures. The book sometimes reads like a series of loosely related blog posts. Most of Geoff Dyer’s comments are whimsical and loaded with judgment, for example, “I hate all gestures associated with finding, lighting and smoking a cigarette.” Such remarks are interruptions that take the reader away from what is essential to the film. The thoughts in this book could have been transformed into three interesting short essays on different topics, perhaps one about the effect Stalker has had on Dyer’s own life, one about how cinema today differs from cinema in the past, and a third about his own anxieties about aging. Each of the essays would call for a different style and tone.The book’s misfortune is that the format and register Dyer uses do not do justice to the multiplicity of topics he attempts to cover.

One subject Dyer spends time on is how personal a film can be. He discusses the impact of the films, showing how they become a part of our biographies, and implies that the experiences we watch are just as formative as the ones we actively participate in. People are changed and shaped not only by what they do, but also by what they see. The book is partly about how people watch films, and how various forms of art expand, and sometimes limit, our capacity for perception. Dyer addresses how movies mix in with our memories, and how they can express the landscape of our dreams. Since the things that happen in movies have analogues in our past and in our daily lives, the past events, memories, and movies all become intertwined. Movies resuscitate our memories, revive them, and even enrich them. They sometimes even become part of them. In this portion of the work, Dyer raises interesting questions about the durability of art, and how it affects us intellectually and emotionally. He shows how movies are removed from and yet ever-present in our everyday lives.

Dyer loves the film Stalker, which he says inspires in him the feeling of “undiminished wonder.” He also loves cinema, and, according to him, “the Zone is cinema – Stalker has long been synonymous both with cinema’s claims to high art and a test of the viewer’s ability to appreciate it as such.” Dyer quotes director Ingmar Bergman: “My discovery of Tarkovsky’s first film was like a miracle.” Dyer himself concludes the book by writing that this film “redeems, makes up for, every pointless bit of gore, every wasted special effect, all the stupidity in every film made before or since.” Yet, despite such high praise, Dyer employs such an ironic tone when writing about the film, poking fun at it and dwelling on its slow pace, ambiguity, obscurity, and what he sees as inconsistencies, that the book will, for the most part, make people who have not seen the film reluctant, if not entirely averse, to the idea. This is not only a paradox but also a shame. It is disrespectful to a subject that Dyer holds in high esteem.

Dyer, rightly, argues that it is a waste to see “Stalker” on a small screen. Yet, it is even more of a waste to read it in a small book, which takes five times longer to read than to watch the actual film. A better use of one’s time would be to see the masterpiece with one’s own eyes. As for the book, it does not dig deep enough to hit the gold, and is therefore not a delight. It doesn’t give the sense of a well-thought out work, and the aftertaste is one of rambling. Engaging with the film lightly, Dyer brushes over what makes the film great. It is a book which will win over the fans of Geoff Dyer, but not those who like and respect Andrei Tarkovsky.

Author Bio:

Elizabeth Pyjov is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.