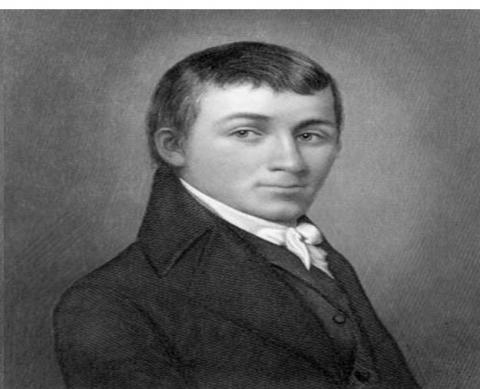

Remembering Charles Brockden Brown, the Father of American Fright

Today's readers are more likely to know of Charles Schultz's beloved Charlie Brown than Charles Brockden Brown. While a great deal of enjoyment can be had from the many strips and cartoon specials with Peanuts, a different pleasure can be found in the gothic novels of Charles Brockden Brown.

While his reputation has diminished, as the first American gothic novelist who wrote about American characters in American settings, he can be considered the father of the tradition. There's much to suggest that America's first professional author might also be one of the more interesting writers of his period, and, as such, has been unjustly relegated to a second tier: he was read on both sides of the Atlantic, with nods and recommendations from the likes of Nathaniel Hawthorne and John Keats; he was an early feminist; and his likely influence on the titanic name in 19th century American gothic tales, Edgar Allan Poe.

Charles Brockden Brown was born in 1771 to a Quaker merchant family in Philadelphia. Throughout the Revolution, Quakers, because of their pacifism, were easily confused with Tories; Brown's family was no different and neither was his city; he sees his father exiled to western Virginia with other Quaker men and Tories for several years. His brothers followed his father into mercantile trades, but Charles trained to be a lawyer, a profession he would later find unsatisfactory. In 1787, Brown formed the Belles Lettres club with eight friends; the club occasionally met in the home of Benjamin Franklin, about whom Brown later writes a poem. For the next few years Brown frequents a variety of intellectual circles, all the while attempting to write fiction. In 1798 that Brown releases his first novel, Skywalk, which is, unfortunately lost to the ages.

For those interested in Brown, Wieland, or The Transformation is probably the best starting point. While it's not Brown's first work, it is his earliest that's available. It is also pleasingly difficult; not for the prose style, but, rather, for its plot structure's use of a narration that, in key sections, is often layered, obscuring the underlying reality and rendering his narrators unreliable.

Within the second chapter, the reader sees this when the narrator, Clara, revisits a formative event in her life, her uncle's account of her father's death. What follows is an account of the spontaneous combustion and subsequent illness of Wieland, the narrator's father, leading to his death. Clara, the narrator, includes, “There was somewhat in his manner that indicated an imperfect tale. My uncle was inclined to believe that half the truth had been suppressed.” None were present with Wieland, and the tale of the beginning of his end is relayed from Wieland to his brother, then from him to Clara; its described reality is thrice removed from the reader, and the narration is rendered unreliable by the layered testimony, some of it hearsay and some of it incomplete, that constructs the event. While it seems a supernatural event, there are clues, in the author's advertisement and the preceding chapters, that all is not as it seems.

This pattern is replicated, though not as extremely, when Clara reads her brother's testimony from his trial (for a quadruple homicide involving his wife and children). Theodore Wieland is, to say the least, unrepentant, “It is true, they were slain by me; they all perished by my hand. The task of vindication is ignoble. What is it that I am called to vindicate? And before whom?” The reader is not just reading the narration of Clara but Theodore's narration through Clara, it is unreliable narrator by proxy — a device Brown uses in later novels, particularly Edgar Huntly. The arrogant testimony of Theodore doesn't seem like it would be out of place from Poe's narrators in “The Black Cat” or “The Tell-Tale Heart.”

In the novel's most suspenseful scenes, the Wielands hear voices of people they cannot see, causing much of the novel's action. Brown assures us that what we normally take for a subjective phenomena has some evidence for being objective. Brown's mastery of suspense is clearly on display in these passages, as it is in the book's dramatic final reveal, when Clara is confronted by her escaped brother, still convinced that the voice of God has told him to kill. The novel is, as so many of its time, a tale with a moral; in this case, it's epistemological and psychological, and it's delivery is a work of terroristic finesse.

Brown's other works, Edgar Huntly and Arthur Mervyn, are similarly ghastly and weird. It is only fitting that the American Republic, birthed in fits of conspiracy and violence, the fear of which was very real for Brown and his family, should produce a talent so expert in the macabre.

As William Hazlitt, among the most prominent British critics of the early 19th century, would write, Browns novels “are full (to disease) of imagination, — but it is forced, violent, and shocking.... Mr. Brown was a man of genius, of strong passion, and active fancy; but his genius was not seconded by early habit, or by surrounding sympathy.”

The American journalist and novelist Margaret Fuller, in 1846, would celebrate the reprinting of Wieland and Ormond, “We rejoice to see these reprints of Brown's novels, as we have long been ashamed that one who ought to be the pride of our country, and who is, in the higher qualities of mind, so far in advance of our other novelists, should have become almost inaccessible to the public.” And this, unfortunately for the aforementioned reading public, was written only 36 years after Brown's 1810 death.

Others who would read Brown and even come to recommend him included Sir Walter Scott and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, perhaps proving that critical judgements of an age's leading litterateurs — sadly — may not be enough to preserve an author's reputation. Later on, in “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” H.P. Lovecraft would write of Brown that, “He had an uncanny atmospheric power which gives his horrors a frightful vitality as long as they remain unexplained.” While he found Wieland's ventriloquial explanation “lame,” Lovecraft did concede “the atmosphere is genuine while it lasts,” which, from a notoriously prodigious man whose work shaped much of horror and science fiction that would come after, seems no idle praise.

Brown's work today is experiencing a sort of comeback thanks to The Charles Brockden Brown Society's conferences and reprinting efforts, although the latter is a little expensive for most tastes. Despite decades of depressed interest, prominent writers are once again taking notice of a man Joyce Carol Oates has lauded as the “first American novelist of substance.” For the historically minded and those with a taste for both the high-minded and the ghastly, the revival of Charles Brockden Brown's reputation, especially as it translates to print runs, and Wieland in particular, will prove a welcome development.

Author Bio:

Adam Gravano is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine