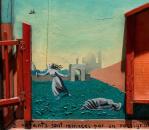

Abderrahmane Sissako’s ‘Timbuktu’ Is a Spellbinding Political Film

Timbuktu

4 stars (out of four)

Not rated

Cohen Media Group

With ardent subtlety of shifting tones, a number of seemingly unconnected subplots, and breathtaking imagery, director Abderrahmane Sissako’s Timbuktu is challenging and oftentimes unbearably honest, which is precisely what makes this film a beautiful and sensational piece of political art, never at the expense of every accolade it boasts and justly deserves. Timbuktu is a powerful study of life at the extremes, defying the audience to rethink their Western-centric views of Islam, its followers and proliferators. With a mixture of satire, comedy, and even melodrama at times, the film dives into the humanity of everyday people in an a vastly misunderstood culture.

Sissako (an African national living in France) sets his story in the desert city of Timbuktu in northern Mali, a territory now under jihadist control. While a number of subplots explore the climate of the city as ruled by religious fundamentalists, the film always swerves back to Kidane, a cattleman who lives in the dunes surrounding the city with his wife Satima, daughter Toya, and Issan, their shepherd.

Under their tent, the camera picks up the modest inner workings of a desert family with touching humility and heart. Though it is but a glimpse of their lives, it is enough to carry the audience all the way through. Horror strikes and Kidane is taken into a swift yet agonizing journey into the justice system of religious law. Meanwhile, a number of vignettes and subplots explore the struggle of the people of Timbuktu as they reshape their lifestyles and beliefs into the regime imposed by the jihadists. In town, music, laughter, and cigarettes have been banned. Women are forced to wear gloves and socks. A couple accused of adultery is stoned to death after being buried neck deep in the sand, and a tragically beautiful scene depicts young men playing with an invisible soccer ball, the game being another banned activity.

At its center, the film exposes the hypocrisy of the jihadist authority and it manages to present it as what it ultimately is: people being in charge of people. Young mujahedeen are more interested in talking about their favorite soccer teams than about Sharia law, and a jihad leader hides behind the desert dunes to smoke. There is a clash of languages that puts in clear perspective the downright absurdity of the authoritarian regime. This is what makes Timbuktu so powerful; not the inherent danger of what it depicts, but that it does it with the humanity that it so fervently seeks. It shows tyrant and afflicted as humans alike, the former driven by something that transcend religious zealotry into the realm of basic human desires for power and greed, purging the reasons behind their keenness. It is meant to grab us by the shoulders and shake us ever so slightly yet with such force that it is impossible to ignore our own radical views. It’s a phenomenal eye-opener.

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.