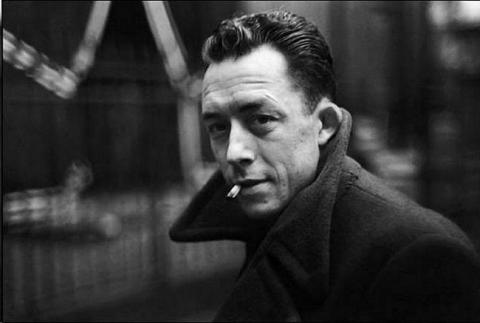

Remembering Albert Camus

He was presumably the most photogenic and charismatic French writer of all time and doubtlessly one of the greatest minds and authors of his century, an expounder, if not hero, of hopelessness and absurdity. On the occasion of his 100th birthday it’s about time we demystify the icon of the incorruptible intellectual, whose magical sentences — pointing fingers that burst the most fundamental dreams of humankind like bubbles — remain unwavering boulders in the word-landscapes of the 20th century.

Born into a world situated on the periphery of history — on a naked loam ground on a winery near the East-Algerian town of Mondovi — to a mother of Spanish origins who was both deaf and illiterate, and a father who died in the Battle of Marne when he was barely one year old, Camus was abandoned to his own fate early on. Although raised in extreme poverty by his domineering grandmother, he attended the lycée and later the University of Algiers, where he completed his undergraduate studies in Philosophy with a thesis on Plotinus and Saint Augustine, before he turned to theater, journalism, and to a literary career that led him to Paris, the city that made him famous, but also feel like a “stranger.” He regretted “the dull and dark years spent in Paris”, as he wrote in 1945.

“Long after Camus left Algeria, his writing remained imbued with his intense love for Algerian landscapes — the mountainous Kabylia, the Roman ruins of coastal Tipasa, the shining port of Algiers, and the modest blue balcony of his mother’s apartment on the rue de Lyon”, writes Alice Kaplan in her introduction to Camus’ recently translated Algerian Chronicles. All of Camus' major works are set in Algeria. The splendid early essays from the books Noces (Nuptials) and L'Envers et l'endroit (Betwixt and Between, also translated as The Wrong Side and the Right Side) celebrate the pact between sun and sea, and the physical and spiritual freedom it fosters.

The world is full of injustices, he stated in his subsequent preface to L'Envers et l'endroit, but there is one in particular that no one talks about: the injustice of climate. Heat and light, the hard and rudimental light of Algeria and Greece and the soft and conciliatory light of Italy and France, are more than just mere indicators of comfort; to Camus they were ways of understanding the world, his artistic source that was nursing his life, what he was and what he said. It is this southern light that made him see the world as if on the first day, liberated from the cellophane that Europe smothered every vital thing with.

The light and the silence of the south were Camus’ cardinal points, steering his wish for a world whose senses will hopefully revive from its anesthesia called politics and culture, its forced fabrication and second-hand nature. The south is his antidote for a Europe, which sacrificed its sense of beauty for intemperance, and smells like office and believes in the ability to buy happiness and store it in a garage. In his book Ete (Summer) he laments: "We are experiencing the time of big cities. Voluntarily we amputated from the world what causes its duration: the nature, the sea, the hills, the tranquility of the evening. "

Although Camus’ geo-poetic Arcadia of intellectual and natural simplicity ranks among Schiller’s Greece or Rimbaud’s Arabia, he was affronted by many contemporaries like Sartre, for example, who attributed a historical oblivion to his yearning. No, Camus wasn’t the type of intellectual who reinvented the (political) wheel as if world history was a novel and the philosopher its author; he was more of a lost apostle who shook at the fundaments of modern life and who rebelled against the ugliness of our cities, while others were willing to resign and see some sort of beauty instead. In the end it was this type of thinking that triumphed over the genius, more educated and philosophically brilliant Sartre who was more interested in his own historical novel than the Soviet Gulag or the old lady next door. On August 8, 1945 Camus was the only French editor-in-chief who expressed his horror at the dropping of the American atom bomb in Hiroshima.

“There is in this man a probity so obvious that it inspires almost immediate respect in me. To put it plainly, he is not like the others” said writer Julien Green of Camus after listening to his lecture. This description seems even more fitting today, in a time of soul coaching and life optimization, and Peter Sloterdijk dictating You must change your life from the bestsellers table at Barnes and Noble. What life has to offer is completely irrelevant to Camus for it all boils down to an “inhuman show in which absurdity, hope and death carry on their dialogue” as he writes in The Myth of Sisyphus, his most famous essay on absurdity, written at the early age of 23. The only important question is if it’s worthwhile: “There is but one truly serious philosophical problem, and that is suicide. Judging whether life is or is not worth living amounts to answering the fundamental question of philosophy. All the rest — whether or not the world has three dimensions, whether the mind has nine or twelve categories — comes afterwards. These are games, one must first answer.”

In Nuptials we will not only find his answer to this question but also a beautiful summary of his philosophy of indifference and humbleness towards creation: “In a moment, when I throw myself down among the absinthe plants to bring their scent into my body, I shall know, appearances to the contrary, that I am fulfilling a truth which is the sun's and which will also be my death's. In a sense, it is indeed my life that I am staking here, a life that tastes of warm stone, that is full of the signs of the sea and the rising song of the crickets. The breeze is cool and the sky blue. I love this life with abandon and wish to speak of it boldly: it makes me proud of my human condition. Yet people have often told me: there's nothing to be proud of. Yes, there is: this sun, this sea, my heart leaping with youth, the salt taste of my body and this vast landscape in which tenderness and glory merge in blue and yellow. It is to conquer this that I need my strength and my resources. Everything here leaves me intact, I surrender nothing of myself, and don no mask: learning patiently and arduously how to live is enough for me, well worth all their arts of living.”

Camus owes his return to the south at the end of his life to the Nobel Prize he won in 1958, which enabled him to purchase a country house in the south of France. In this refugium he began working on his last project: The First Man, a novel he felt he was born to write and whose manuscript was found covered in mud near the accident scene, a few days after his fatal car crash in 1960.

Author Bio:

Karolina Swasey is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

Photos: Mitmensch 0812 (Flickr); Wikipedia Commons.