Philanthropy and Generosity: The Legacy of C.J. Walker

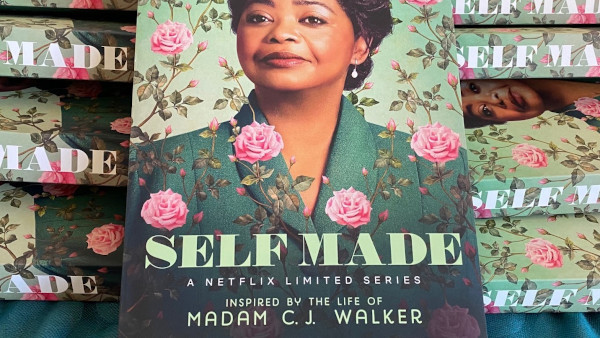

The Netflix series, Self Made: Inspired by the Life of Madam C.J. Walker, brings to life part of a fascinating rags-to-riches tale I’ve been researching for several years.

Walker, widely documented to have been America’s first self-made female millionaire, made her fortune building an Indianapolis-based beauty products company that served black women across the U.S. and overseas. Today it offers a product line through Sephora.

Oscar-winner Octavia Spencer stars in the miniseries about the African-American entrepreneur originally named Sarah Breedlove. Born shortly after emancipation in 1867 on a cotton plantation in Louisiana to a formerly enslaved family, she later adapted the initials and last name of her third husband – played by Blair Underwood in the series. The show imagines Walker’s struggles and successes in a dramatic reinterpretation of the historical record.

I’ve been studying Walker’s archival collections for my upcoming book, Madam C.J. Walker’s Gospel of Giving: Black Women’s Philanthropy during Jim Crow, and speaking about her to audiences around the country for years. I screened the series with great anticipation of how her lifelong generosity and activism would be portrayed in this account that Indianapolis Monthly described as having “fictional characters, invented moments, and a few surreal sequences.”

Her philanthropic legacy didn’t make the cut – aside from a few visual footnotes just before final credits roll. Those footnotes touch on her charitable giving to black colleges, social services and activism with the NAACP.

While viewers will enjoy the series, I want them to learn that Walker didn’t just live a life of hard-won opulence. She exemplified black women’s generosity. Her philanthropy and activism imbued every aspect of her daily life. “I am not and never have been ‘close-fisted,’ for all who know me will tell you that I am a liberal-hearted woman,” Walker told the audience of the 1913 National Negro League Business meeting sponsored by prominent black leader Booker T. Washington.

More than money

Walker distinguished herself on a philanthropic landscape dominated by white people. Men like John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie turned to large-scale philanthropy after spending their lives accumulating wealth. In contrast, Walker’s giving began in earnest when she was a poor, young, widowed mother struggling in St. Louis. She gave along the way from what she had, rather than waiting.

She had much in common with other black churchwomen, club women, educators and activists. Like Mary McLeod Bethune, Nannie Helen Burroughs and Ida B. Wells-Barnett – and tens of thousands of other working and middle-class black women – Walker embodied a versatile generosity that sought to meet communal needs and topple widespread discrimination.

Treasure

Walker was a highly prized donor in the black community. Constantly solicited, she gave money to black-serving organizations across the Midwest and the South.

The Netflix miniseries briefly references her gifts to social services. She supported organizations like Flanner House in Indianapolis, which helped African-Americans get jobs, an education and childcare. She made sure that poor families could eat at Christmastime.

The “Indianapolis Freeman,” a black newspaper, reported in 1915 how her company’s office resembled a grocery store due to all the gift baskets that were filled with food. In 1918, she gave US$500 to support the National Association of Colored Women’s campaign to purchase and preserve Cedar Hill, home of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, which still stands today in Washington, D.C.

Walker lacked formal education but she was a lifelong learner who donated thousands of dollars to the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama and other black schools.

She also patronized the arts, supporting Indianapolis painters such as William Edouard Scott and John Wesley Hardrick, whom she wanted to help gain national stature as an artist.

Time and talent

In addition, Walker belonged to important networks of women that were advancing the cause of freedom from the Jim Crow era’s racism and sexism.

She helped the poor through the Mite Missionary Society of St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church in St. Louis. She supported the National Association of Colored Women, which provided educational and social services to black communities around the country, and advocated for changing public policies.

Author Bio:

Tyrone McKinely Freeman is the Assistant Professor of Philanthropic Studies, Director of Undergraduate Programs, Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, IUPUI.

This is an excerpt from the article, “Netflix’s Self-Made miniseries about Madam C.J. Walker leaves out the mark she made through generosity,” written by Tyrone McKinely Freeman for the Conversation. Read the rest here.

Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

--Netflix

--Wikimedia.org (Creative Commons)

--Children’s Museum of Minneapolis (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons)